A separate timeline

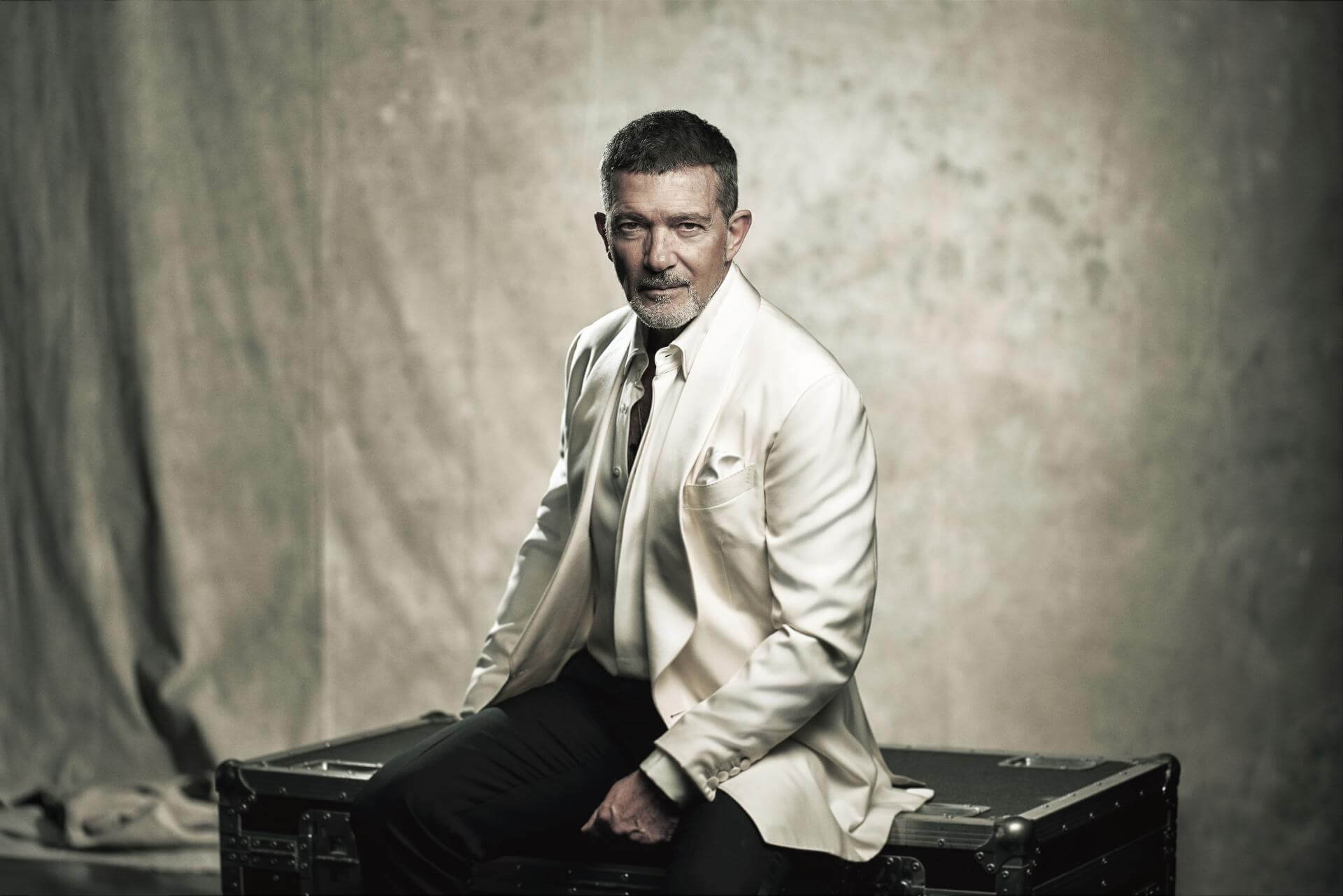

A common fallacy, peddled on Wikipedia and elsewhere, is that Madonna, who had a well-documented crush on the actor in the 1990s, introduced Banderas to Hollywood. Banderas says he “wouldn’t count” meeting Madge as a catalyst moment in his life. “It didn’t have so much meaning,” he says. “It’s true that I met her here in Spain, at a dinner with all of Pedro Almodóvar’s people. But I’d already done The Mambo Kings and Desperado. I never had a relationship with Madonna. I think my agent was very smart at the time. He says, ‘You’ve got a career already in America, you have done a couple of movies, don’t go there. Have dinner with her, whatever, because she invited you, but don’t get involved there, because everybody’s going to think whatever happens to you now is because of her’. When we did Evita we became friends, actually, but that was it. That was it. The last time I saw her was 10 years ago, maybe.”

Most people would consider Philadelphia Banderas’s major Hollywood breakthrough. Shortly afterwards came 1993’s The House of the Spirits alongside Meryl Streep, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close and Winona Ryder, then 1994’s Interview with the Vampire, sharing a bill with Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise and Kirsten Dunst. By now Banderas’s star was soaring (and his English improving: “In The Mambo Kings, I said my lines phonetically — when I saw the movie for the first time I couldn’t understand everything,” he says). A turn opposite Sylvester Stallone in 1995’s Assassins; as Che Guevara in Evita, with Madonna (1996); the first of his two turns as the swashbuckling pulp hero Zorro (1998); and in John ‘Die Hard’ McTiernan’s historical drama The 13th Warrior (1999) would all follow before the decade was out.

Banderas’s Hollywood star has never faded since, thanks to acclaimed performances in movies ranging from the underrated (Woody Allen’s 2010 comedy You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger; Brian De Palma’s 2002 sexy noir tribute Femme Fatale) to the critically panned (Steven Soderbergh’s 2019 take on the Panama Papers saga, The Laundromat) and the sublime (Spanish-language black comedy Official Competition, in which he co-starred with his longstanding friend Penélope Cruz). Lest we forget, that cutlass- wielding feline got his own flick in 2022, and Banderas also lent his voice to this year’s instalment of the Paddington franchise.

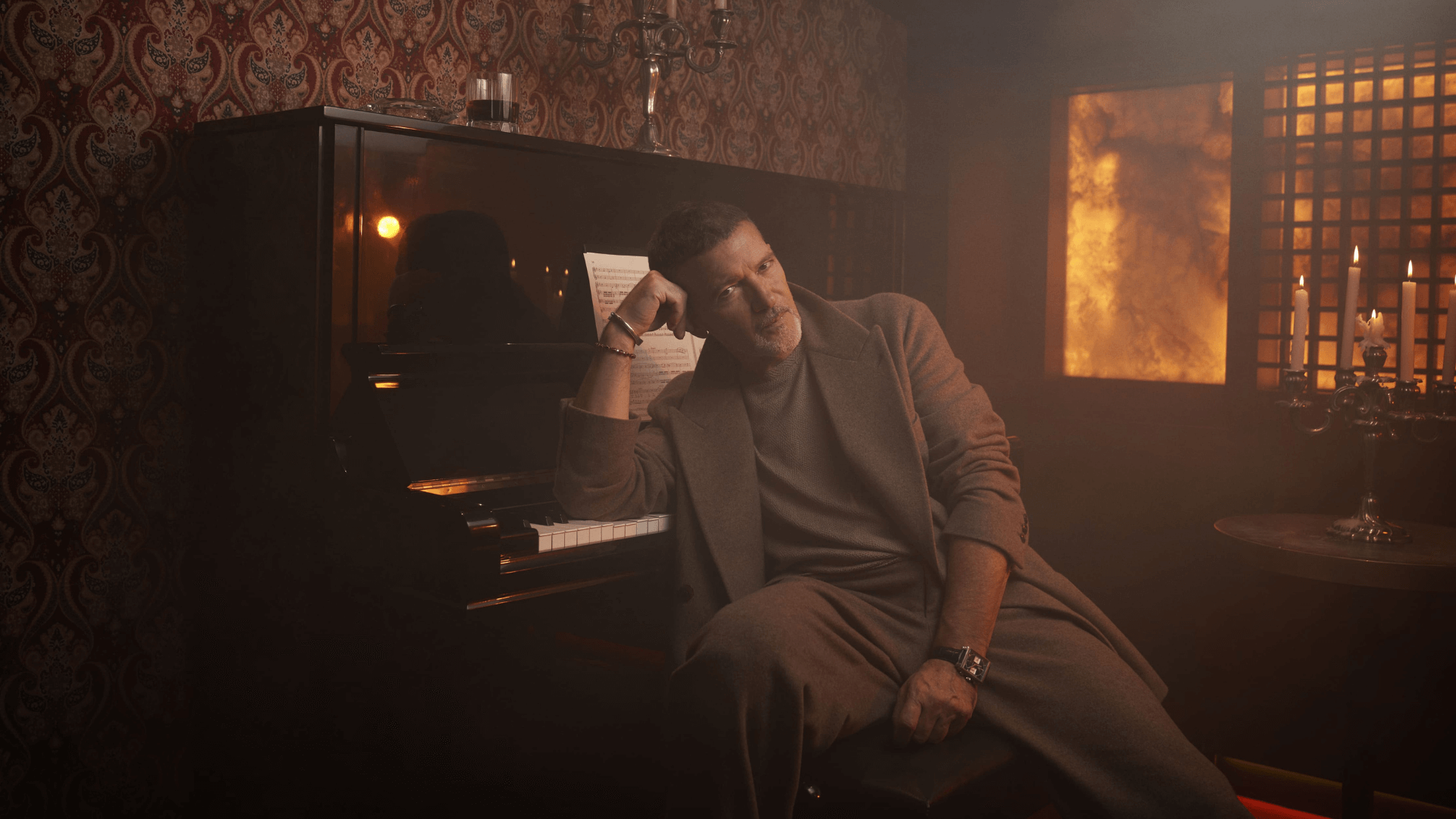

But for those who favour the arthouse over the multiplex, a separate timeline exists in Banderas’s film career, beginning in the early 1980s with a chance meeting on a terrace outside Madrid’s Café Gijón before a performance of La Hija Del Aire (‘The Daughter of the Air’) by Pedro Calderón de la Barca. “You have a very romantic face,” a then obscure avant-garde director sporting an elaborate bouffant and carrying a red briefcase is said to have remarked to the then 20-year-old impoverished actor. “You should do movies.” The director in question, a film-scholar darling-in-the-making, was Pedro Almodóvar. He cast Banderas in Laberinto de Pasiones (‘Labyrinth of Passion’), a screwball sex comedy and an audacious dash of post-Franco counterculture, in 1982. It would become the first of eight movies to date that they have worked on together. The most critically acclaimed of these — 2019’s semi- autobiographical Pain and Glory — earned Banderas an Academy award nomination for his portrayal of a heroin-abusing quasi-version of Almodóvar. Arguably the most chilling is The Skin I Live In, a 2011 psycho-sexual thriller based loosely on the novel Tarantula by Thierry Jonquet, about a plastic surgeon who has performed illegal transgenic surgery on his lover (Almodóvar has described the film as “a horror story without screams or frights”). But

for Banderas, it’s a much earlier movie — a kind of retelling of Beauty and the Beast, with Stockholm Syndrome a major theme and lashings of wince-inducing violence — that audiences of a sensitive nature most blench at. “There is a number of movies I have done in the past, with Almodóvar especially, that would be forbidden today,” he says, “and if we did Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! today, it would be a scandal. But in 1988 it was not a scandal. It was a very interesting reflection on relationships between women. People just connected to it in a very interesting way. Now, that would be almost impossible to do. So what has changed? We are different.”

How art stands up to changing societal values is an issue that, Banderas says, raises many existential questions. “Where are we going, what have we left behind, what do we lose, what do we gain?” he asks. I put it to him that even Philadelphia, lauded for its sensitive tackling of the Aids taboo and homophobia, might today be criticised, by some, for portraying HIV as essentially a homosexual disease. “Oh, yes, absolutely,” he says, citing as another example the 1939 classic Gone with the Wind being removed from U.S. streaming service HBO Max in 2020. “[We’re asked to] take the carpet and just brush everything under it,” he says. “The film has one of the most strong women in the history of motion pictures. Do you eliminate that? There were women like that at that time in Atlanta — but also, there was slavery. People were slaves. We shouldn’t forget that!”

Banderas also makes an interesting distinction between ‘colourblind’ casting decisions with existing classics from the cultural canon and doing so with an entirely new theatrical concept, such as Hamilton: An American Musical, the hip-hop Broadway show in which young black, Asian and Latino actors portray the ageing white Founding Fathers. “That’s very interesting, because the concept was originated like that,” he says. “It’s winking its eye at you from the first second of the play and the audience sees that George Washington is black. It’s good. But if we go back in time and we just take something and completely change it... ”

Interestingly — this shows how much thought he’s put into the issue, and tells us about Banderas as a dramatist — when it comes to directing Gypsy, he says he has discarded faithful recreations of how spicy Gypsy Rose Lee’s striptease performances were in favour of those that replicate, more accurately, how Lee’s audiences reacted in that era. “The striptease that is performed every night here is stronger than it was in the 1930s,” he says, “so that what I’m showing you, it will make an audience today feel the same impact that probably was felt in 1930 with Gypsy Rose Lee when she just showed her boobies — which was, ‘Woah!’ at that time.”

.svg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)